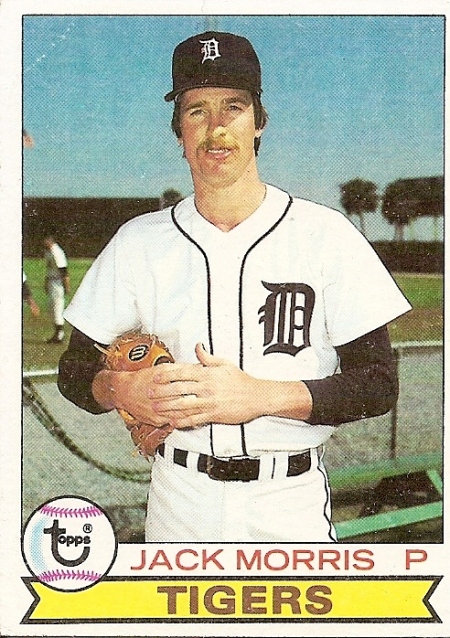

Jack Morris

With a competitive, sometimes combative, spirit and a devastating split-fingered fastball, Jack Morris became the pitcher of the 1980s and continued his dominance into the early 1990s. His 162 victories in the 1980s were 22 more than runner-up Dave Stieb of Toronto.

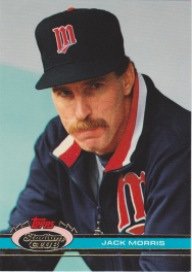

Four times he was a member of a world-championship team, including a one-year stint in his home state, pitching a 10-inning shutout in the final game of the 1991 World Series for the Minnesota Twins. He finished his career with more than 250 wins.

John Scott Morris was born May 16, 1955 in St. Paul, Minnesota, and grew up watching the Minnesota Twins at Metropolitan Stadium in suburban Bloomington. He also remembers a television being wheeled into his grade-school classroom so they could watch the 1965 World Series, which the Twins lost in seven games to the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Morris’s dad, Arvid, was an electronic technician for Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing (which became 3M), and his mom, Dona, was a housewife. Arvid and Dona now live in Grand Rapids in northern Minnesota, after their son helped Arvid retire early from 3M “thanks to baseball.” Morris has an older sister, Marsha, and a younger brother, Tom, a lefthanded pitcher who was a college teammate for one year and later spent two seasons in the minor leagues. (Tom was drafted by the Twins in 1978 but did not sign; he then pitched two years for Quad City in the Cubs organization.)

The family lived in several Twin Cities suburbs as Morris grew up before settling into the Highland Park neighborhood of St. Paul. In addition to baseball, Morris was a ski jumper for the St. Paul ski club when he was in junior high and played on the varsity basketball team for Highland Park High School. On the diamond, Morris was a third baseman and shortstop. With better control than his older brother, Tom was the top pitcher at Highland Park, and Jack’s appearances on the mound in high school and on his American Legion team were relatively rare.1

“He could throw hard enough to knock down the backstop in high school,” said Bill Lorenz, Morris’s baseball coach at Highland Park. “He just couldn’t hit the backstop.”2

However, because of his strong arm, he was recruited by coach Glen Tuckett and given a scholarship to pitch for Brigham Young University (BYU) in Provo, Utah. “When I saw that arm, I lit up like a pinball machine,” said BYU athletic director and former baseball coach Glen Tuckett.3

Until his senior year, Morris had hoped to pitch for the Minnesota Gophers under longtime coach Dick Siebert. “All through high school that’s [Minnesota] where I wanted to play,” he said. However, the Gophers did not recruit Morris. In addition, Morris took a closer look at the Gophers’ yearly schedules and realized how short it was. The Gophers at that time were making one southern trip a year, and, before the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome was built, the team could not start its home schedule until April, leaving barely two months to play.

“I wanted to play for a baseball school where they played in good weather and good teams,” Morris explained. He applied and was accepted at Arizona, Arizona State, Florida State, but he would have been a walk-on. Then BYU offered a scholarship. They would play a schedule with Arizona, Arizona State, Cal State Fullerton, Hawaii. “The schedule was phenomenal. I knew I would get exposure. That’s why I went there.”4

Morris lettered with the Cougars in 1975 and 1976. His Brigham Young teammates included his brother (who, unlike Jack, made the team as a freshman) for two years; Cam Killebrew, son of future Hall of Famer Harmon Killebrew; and Vance Law, who went on to the major leagues and later came back to Brigham Young as its head baseball coach. Law’s dad, Vernon Law, a 16-year major-league veteran who had won the Cy Young Award in 1960, worked with the Brigham Young pitchers in the 1970s. A 16-year major-league veteran who had won the Cy Young Award in 1960, Law helped transform Morris from a youngster with a strong but erratic arm into an accomplished pitcher who was drafted after his junior season in 1976 in the fifth round by the Detroit Tigers.5

Morris was assigned to the Tigers’ Class-AA farm team in Montgomery in the Southern League, where he struggled with his control. Morris walked a batter an inning and had a 6.25 earned-run average (ERA) in 36 innings pitched in 1976. Nevertheless, he was promoted to the Triple-A level in 1977.

Pitching for Evansville in the American Association, Morris lowered his walks and upped his strikeouts (both on a per-inning basis) in 20 starts with the Triplets. Morris got the call to the big leagues when the Tigers put Mark Fidrych, who had won 19 games as a rookie in 1976 but had knee and arm problems in 1977, on the disabled list.

Morris made his debut in Chicago July 26, relieving Dave Roberts in the fourth inning with the Tigers behind, 6-2. He inherited a runner at first base with no out but got out of the inning without it scoring. Morris pitched four innings and allowed two runs as the Tigers lost, 8-3. Five days later, he got his first start, pitching against Bert Blyleven in Texas. Morris allowed two runs in the first inning but gave up only three hits and no runs after that as he pitched nine innings, walking five batters and striking out 11. Both he and Blyleven went nine innings, and neither got a decision as the Rangers won in 10 innings.

Morris stayed in the starting rotation, winning one and losing one over the next month. However, he also had some arm problems. The Tigers, after the situation with Fidrych, had become protective of their young pitchers and, at the end of August, shut Morris down for the season. “He’s too good a prospect to fool with,” said Tigers manager Ralph Houk.6

Morris was back in 1978, but he was again limited by arm problems and finished the year with a won-lost record of 3-5. In 1979, he didn’t even make the team out of spring training and was sent back to Evansville. However, he wasn’t expected to stay long in the minors. “You better get a good look at him now,” said Evansville Manager Jim Leyland, “because he won’t be here in a month.”7

Leyland’s prediction was accurate because Morris was back in Detroit, this time for good, making his first start for the Tigers May 13. Despite the delayed arrival with the Tigers, Morris won 17 games and had an ERA of 3.28, fifth-best in the American League.

To this point, Morris had relied on a standard repertoire of a fastball, slider, and change-up. In the early 1980s, he began having some problems with his slider and was on the lookout for a new pitch. “My slider started flattening out. I couldn’t get the big break anymore. I was having some inconsistency with my slider, hanging a few too many. I was looking for that ‘out’ pitch. My fastball was still good, change-up was still good, but I was looking for that ‘strike three’ pitch.”

It was about that time he discovered the forkball, or split-fingered fastball. Although his pitching coach with the Tigers, Roger Craig, is often credited with teaching him the splitter, Morris says the credit belongs to his Tigers teammate, Milt Wilcox. In the Chicago Cubs organization in the mid-1970s, Wilcox had crossed paths with Bruce Sutter, who would make a Hall of Fame career out of the splitter. “He watched Sutter throw it,” Morris said of Wilcox. “He [Wilcox] couldn’t throw it himself because his fingers were too short.” One day Morris was throwing in the bullpen when Wilcox asked if he’d like to try the forkball. “I threw about eight or nine pitches and nothing happened.” Morris was ready to give up, but Wilcox suggested some adjustments with the grip and release. “I threw one and the bottom dropped out. I thought, ‘I gotta work on this thing because this is ridiculously nasty.’ And I threw about six more in a row that all worked the same way. . . . I saw what this thing could do, and I said, ‘I’ve got to master this thing.’”

Morris said he started working on the pitch at the end of the 1982 season and started throwing it regularly in 1983, the first year he won 20 games. “In 1983 and 1984, I pretty much had it to myself in the American League. It was a total gift. It was like nobody knew it was coming. It was awesome. It was so much fun. And then everyone else started trying to learn how to pitch and then hitters started to adjust to it. My forkball was above average. I could almost tell guys it was coming, and they still couldn’t hit it. . . . When I threw it right, nobody hit it.”8

Led by Morris, the Tigers got off to a great start in 1984, winning their first nine games and 16 of their first 17. Morris had four of the team’s wins in that opening run. He pitched the season opener in Minnesota, where he had never lost a game in the majors, and won, 8-1.

Four days later, on a cold and wet day in Chicago, Morris was unhittable. After eight innings, the Tigers had a 4-0 lead, and Morris hadn’t allowed a hit. As he sat in the dugout in the top of the ninth, his teammates stayed away from him, following the superstitious tradition of not mentioning that a no-hitter was in progress. However, Morris broke the silence and declared, “I’m going to do it.” On his way back to the mound, he turned toward a couple hecklers and said, “Just watch.”9

He retired the first two White Sox batters and went to a 3-2 count on Greg Luzinski. The next pitch was close, but plate umpire Durwood Merrill called it a ball. Even many of the partisan Chicago fans, hoping to see a no-hitter, howled in protest. But Morris got ahead of the next batter, Ron Kittle, then came in with a splitter. The pitch was low, but Kittle bit, trying to hold up but going too far with his swing. Morris had his no-hitter, the first for the Tigers since Jim Bunning had no-hit the Boston Red Sox in 1958.

Morris won 10 of his first 11 decisions in 1984, and, for a time, all was well. However, he missed two starts in June with a sore elbow. He won his first game back but then lost three in a row, dropping his season record to 12-6.

Morris battled with umpires, sometimes blaming them for his problems, as well as with his teammates. He resigned as the team’s player representative and quit talking to the press, which had already dubbed him “Mount Morris” for his sometimes explosive temper. Roger Craig publicly said Morris should “quit acting like a baby,” and relations with his fellow players weren’t much better.10

However, as Morris regained his form on the mound, he began talking with the press again and healed other rifts as the Tigers cruised to the American League East title and went on to win the World Series. Morris went the distance and won both his starts in the World Series as the Tigers beat the San Diego Padres, four games to one.

In 1986, Morris posted a 21-8 won-lost record with a 3.27 ERA in 267 innings. His 21 wins were second in the American League, behind Roger Clemens, and he led the league with six shutouts while finishing fifth in the voting for the Cy Young Award. Morris’s contract with the Tigers was up after the season, making him one of the top free agents on the market.

Fans in Morris’s home state were excited about the possibility of him pitching for the Twins as he came to Minnesota in late 1986 to talk with the team’s owner, Carl Pohlad, and new general manager Andy MacPhail. However, Morris left without the parties reaching an agreement on a contract.

Morris and his agent, Dick Moss, had presented four proposals, including one for a two-year contract in which the salary would be determined by an arbitrator. MacPhail later decried the take-it-or-leave-it approach of Moss and Morris, who had also drawn some criticism for his opulent attire that day, a full-length fur coat.11

In reality, however, it was unlikely the Twins would have signed Morris, since major-league teams, operating in concert, had adopted a hands-off policy with regard to signing free agents from other teams for the purpose of keeping salaries down. (Arbitrators later determined that teams had conspired against free agents over the course of three off-seasons, and the owners had to agree to establish a $280 million fund to distribute to the players affected by the collusion.)12

“No, there was no chance of signing,” Morris said of his negotiations with the Twins and the role of collusion. He said he had once been asked if he would ever write a book about his career and added, “If I ever did, it would be about the collusion years in baseball. Nobody has talked about it, it has been pushed under the table. I led the charge in that whole thing, and I understood it better than anyone else. I was the premier pitcher in baseball, and I couldn’t get a nickel, couldn’t get a penny.

“I had actually almost agreed to terms with Mr. Pohlad when Andy MacPhail stepped out of the room. My agent and I had a few minutes to talk alone with Carl, and Carl pretty much agreed to a contract. Andy came back and excused us and told Carl there was no way he could sign me. That in itself defines what was going on. Andy was on the phone with somebody, and somebody told him, ‘Nobody gets signed.’ And that’s the end of that story.”13

Morris re-signed with Detroit for the 1987 season and, with a record of 18-11, helped the Tigers win the East Division title with a record of 98-64. However, the Tigers lost in the playoffs to the Minnesota Twins. Morris lost his only start in the series, which was also the first time he had lost in Minnesota as a member of the Tigers. (Morris had been the losing pitcher for the American League in the 1985 All-Star Game at the Metrodome in Minneapolis.)

The Twins went on to win the World Series, and Morris noted that he could have been a member of that championship team if not for collusion. However, he got his chance to pitch for the Twins, and for the championship, a few years later.

In the meantime, he went through a couple of losing seasons. His 1989 season included elbow surgery for a stress fracture, and he finished with a record of 6-14. Despite four straight wins at the end of the year, he finished the 1990 season with a record of 15-18. However, he was second in the American League in innings pitched (and tied for second in the majors) and demonstrated that he could still be counted on as a workhorse.

He could also still be Mount Morris, at least at times. A noted incident during the 1990 season was Morris’s response to Jennifer Frey, a sportswriter intern of the Detroit Free Press. Even though Frey was a credentialed member of the Detroit chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America, Morris did not appreciate her presence in the locker room and let her know it.14

Morris later said of the incident, “That was totally blown out of proportion. It was a situation where a woman was not supposed to be in the locker room. She was.” [Note: The right of female reporters to have the same access to locker rooms as male reporters had been established in court cases as far back as the late 1970s.15]

“I reacted very poorly,” Morris acknowledged.16

Morris was a free agent again after the 1990 season. With collusion by this time a thing of the past, Morris finally signed with the Minnesota Twins for 1991. He had turned down a three-year contract worth more than $9 million from the Tigers to sign for a guaranteed salary of $3 million a year with the Twins and the chance to earn more based on incentives. The contract he signed also allowed him the option to become a free agent after the end of each season.

Morris was emotional as he talked about how much it meant to sign with his hometown team. He even shed a few tears, an act that would be held against him by many local fans within a year.17

Morris was emotional as he talked about how much it meant to sign with his hometown team. He even shed a few tears, an act that would be held against him by many local fans within a year.17

For the 1991 season, Morris was outstanding, posting an 18-12 won-lost record while leading the team with 246-2/3 innings pitched. The Twins, after having finished in last place in 1990, won the American League West title. Morris got the call for the opening game of the league playoffs. He won that game, as well as Game Four, and the Twins defeated the Toronto Blue Jays, four games to one, to advance to the World Series. Their opponents would be the Atlanta Braves, another team that had finished last the season before.

Morris won the series opener against the Braves, and did not get a decision in Game Four, which the Twins lost. The series went to a decisive seventh game, and Morris was on the mound again with John Smoltz pitching for Atlanta.

The aces matched shutout innings over the first half of the game, but Morris found himself in a jam in the fifth as the Braves put runners at first and third with one out. But Morris used his split-fingered fastball to get Terry Pendleton to pop out and then went to a full count on Ron Gant. Morris placed a fastball right where he wanted it, on the low-outside corner, freezing Gant with a called third strike to end the inning.

The game remained scoreless into the eighth, when the Braves mounted an even greater threat, putting runners at second and third with no out.

While Twins fans were sweating, Morris later said he was still calm. “I never had a negative thought,” he maintained. “I’m such a positive thinker, I never really felt like I was in trouble. It was my will that carried me through the game.”18

Morris needed every bit of his will, as well as his nasty splitter, as Gant stepped to the plate. Gant had stranded a pair of runners in each of his previous two at-bats, although this time, with no out, even an out could bring in a run. Minnesota responded by pulling in its infield. Gant popped the first pitch foul, then went after a splitter on the outside part of the plate, resulting in a feeble grounder down the first-base line. First-baseman Kent Hrbek fielded it and kept his eyes on Lonnie Smith, making sure he held at third, as he tagged Gant for the first out.

Getting Gant was the key to the inning as it now allowed the Twins to walk the dangerous David Justice to load the bases, set up a double-play, and bring Sid Bream to the plate. Bream pulled a 1-and-2 pitch to Hrbek, who fired home to start an inning-ending first-to-home-to-first double play.

Past the jam, Morris appeared stronger, putting down the Braves in order on eight pitches in the ninth. Manager Tom Kelly planned to send reliever Rick Aguilera out for the 10th inning, figuring Morris, with 118 pitches to that point, had had enough. But Morris told Kelly, “I’m not going anywhere. This is my game.”19

Morris later said that, after getting out of the eighth inning, “I was getting stronger. I just felt like I could have gone another six, seven, eight more innings. I was getting stronger as the game went on.”

Morris retired the Braves on eight pitches again in the 10th inning. In the bottom of the inning, the Twins finally scored to win the game, 1-0, and the World Series.

“I probably had the best mindset in that game that I’ve had in any game in my whole career, and that’s because I didn’t allow negative thoughts into my game,” Morris said. “Even when I was in trouble, I didn’t acknowledge trouble. I just said, ‘Well, I’ll get this next guy. We’re going to win this game.’ If I could bottle that, I’d be the richest man in the world. If I could bottle it and sell it to athletes or sell it to businessmen or whatever, it would be a phenomenal thing. I can’t hardly even describe it, but I can tell you it was something I had never experienced before and really never experienced again.”20

Minnesota fans celebrated their second world championship in five seasons, but the man largely responsible for the title would not be back with the Twins. He exercised his option to become a free agent after the season and signed with the Toronto Blue Jays. Reaction from Minnesota media members and fans was sharp, and his tearful press conference when he had signed with the Twins less than a year before was held against him by many.21

Morris said the difference in contract offers by the Twins to retain him and the Blue Jays to acquire him “wasn’t close.” Morris said Carl Pohlad made it clear that the team was looking ahead to re-signing the team’s star, Kirby Puckett, after the 1992 season and were conserving money for that purpose.

“I never wanted to leave here,” Morris said. “I never wanted to leave Detroit [after the 1990 season]. Had Detroit taken care of me the way I felt I should have been taken care of in Detroit, I never would have left Detroit.”22

In Toronto, Morris played on two more world championship teams. He was 21-6 in 1992, but arm troubles hampered his 1993 season. He didn’t pitch in the World Series that year, and the Blue Jays released him at the end of the season. Morris signed with the Cleveland Indians for 1994 and had a 10-6 record before a players’ strike ended the season.

Morris tried but failed to catch on with the Cincinnati Reds in 1995. Confident he could still pitch, Morris made a comeback in 1996 with the St. Paul Saints, a local team playing in an independent professional league. “The Twins needed pitching bad, and I wanted to come back and maybe finish my career right here again,” said Morris. “But they didn’t come across the street to even look at me. I guess they were still mad that I left. I don’t know what happened there.

One of Morris’s teammates on the Saints was another player looking to make it back to the majors, Darryl Strawberry, who ended up being signed off the St. Paul roster by the New York Yankees. “I had a chance to go to New York with Strawberry, and at the time I didn’t want to play for the Yankees,” Morris said. I regret that today. If I had one thing to go back and do again, I would have signed with the Yankees and probably put two or three more [championship] rings on my finger.”23

Morris is now back with the Minnesota Twins organization, working as an analyst on the team’s radio broadcasts. He and his wife, Jennifer, have a son, Miles. Morris also has two grown children, Austin and Erik, from a previous marriage.

“Life is good,” he says. “I’m a very lucky person. I have my health, I have a very loving family and an organization I’m very happy to be working for. If there was any animosity between us [Morris and the Twins] for leaving . . . all those bridges have been mended, and I’m very happy to be here, and I think they’re very happy to have me here, and I think it’s a good relationship.”24

Last revised: November 29, 2021

Sources

A number of sources for basic statistical information were used, including The Baseball Encyclopedia, Tenth Edition, (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1996), Total Baseball, Sixth Edition, edited by John Thorn, Pete Palmer, Michael Gershman, and David Pietrusza with Matthew Silverman and Sean Lahman (Kingston, New York: Total Sports, 1999) as well as from Baseball-Reference.com and annual guides published by The Sporting News.

Another source was Retrosheet with play-by-play being available from its web site (http://retrosheet.org) or directly from Retrosheet founder Dave Smith. The information used was obtained free of charge and is copyrighted by Retrosheet. Interested parties may contact Retrosheet at 20 Sunset Road, Newark, Delaware 19711.

Notes

1 Interview with Jack Morris, Minneapolis, May 27, 2007.

2 Dennis Brackin. “Morris Good Pitcher, Better Competitor,” Minneapolis Star and Tribune, May 24, 1987: 10C.

3 Brackin.

4 Interview, May 27, 2007.

5 Interview, May 27, 2007. Statistics and materials provided by the Athletic Communications Department of Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

6 “Tito, at 33, Truly a Tiger on Triples,” Jim Hawkins, The Sporting News, October 1, 1977: 11.

7 “Momentary Morris,” The Sporting News, May 12, 1979, p. 37.

8 Interview, May 27, 2007.

9 Interview, May 27, 2007; Tom Gage, “Morris’ Masterpiece Silences White Sox,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1984, p. 25.

10 “Sour Morris Buttons Lip” by Tom Gage, The Sporting News, August 6, 1984: 14; “Morris Finally Unbuttons Lip” by Tom Gage, The Sporting News, September 17, 1984: 12.

11 Howard Sinker, “Twins to Morris: Hit the Road, Jack,” Minneapolis Star and Tribune, December 17, 1986: 1D.

12 1987 Speech by Andy MacPhail to the St. Paul Old Timers’ Hot Stove League Banquet, January 28, 1987.

13 Interview, May 27, 2007.

14 “Women Not Welcome,” Sports Illustrated, August 20, 1990: 15.

15 Email correspondence with Jennifer Frey, May 2007; Court case allowing women access to locker rooms: Melissa Ludtke and Time, Inc., Plaintiffs, v. Bowie Kuhn, Commissioner of Baseball, United States District Court, Southern District of New York, 461 F. Supp. 86, September 25, 1978; Ralph Ray, “Women Writers Win Access to Yank Clubhouse,” The Sporting News, October 14, 1978: 36.

16 Interviews with Jack Morris, May 27 and June 10, 2007.

17 Dennis Brackin, “Comin’ at Ya: Winning Is Everything for Ultra-competitive Morris,” Minneapolis Star and Tribune, February 6, 1991: 1C.

18 Interview with Jack Morris, July 11, 2002 in Milwaukee following Major League Baseball’s press conference to name the most memorable moments in history of the game.

19 Interview, May 27, 2007.

20 Interview, May 27, 2007.

21 Jon Roe, “Money Talks, Morris Walks: Toronto’s $10 Million Offer Lands Righthander,” Minneapolis Star and Tribune, December 19, 1991: 1C.

22 Interview, May 27, 2007.

23 Interview, May 27, 2007.

24 Interview, May 27, 2007.

Full Name

John Scott Morris

Born

May 16, 1955 at St. Paul, MN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.